Today, February 8th …

The eighteenth century English country parson James Woodforde enjoyed a comfortable living from his curacy in Norfolk. The small holdings attached to his position made his household virtually self-sufficient, and the diary he kept for four decades is rich with detail of village and rural life of the time. He recorded anecdotes about harvesting, pig-rearing, fishing, bread making, preserving, and all manner of other farm and domestic duties. His dinner on this day in 1792 was “boiled Leg of Pork and Peas Pudding, a rost Rabbit and Damson Tarts”, and we can be confident that he knew intimately the source of every ingredient.

What an idyllic life! Producing one’s own natural, organic food in the peace of the countryside, completely in rhythm with the seasons. Fresh, wholesome produce. No added food miles. Simple, healthy, and stress-free.

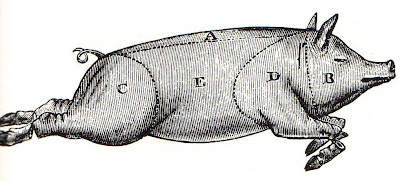

Unless you are queasy about actually murdering your own sweet, fat little piglet with your own hands of course.

Unless you have no clue as to how to choose a good piece of fresh pork if you are unable to kill your own - thereby risking falling victim to an unscrupulous butcher trying to off-load stock from his unrefrigerated shop.

Unless you are (Heaven forbid!) lacking in that skill essential to well-bred men – skill at carving efficiently and elegantly – thus rendering yourself “disagreeable and ridiculous to others”.

Unless you have a terrible craving for lamb, but it is out of season, and anyway you have to keep eating that damned pig you killed a few days ago, even though you are sick of the sight of pork, because there is a lot left and it won’t keep much longer.

Luckily, there are plenty of eighteenth century manuals to help you, should you decide to take up this idyllic lifestyle.

A book with the instantly reassuring title of The ladies’ library: or, encyclopedia of female knowledge, in every branch of domestic economy ... In which is included a vast fund of miscellaneous information (1790) begins the recipe ‘To Roast a Pig’ with the instruction: ‘Stick your pig just above the breast-bone, running your knife to the heart; when it is dead, put it in cold water for a few minutes, then rub it all over with a little rosin beat exceeding fine and its own blood …’. So now you know how to perform that little duty.

If you are forced to obtain your pork from the market, John Trusler gave plenty of advice in his book The honours of the table, published in 1788.

Pork.

If it be young, in pinching the lean between your fingers, it will break, and if you nip the skin with your nails, it will dent. But if the fat be soft and pulpy like lard, if the lean be tough, and the fat flabby and spungy, and the skin be so hard that you cannot nip it with your nails, you may be sure it is old.

To know fresh-killed pork from such as is not, put your finger under the bone that comes out of the leg or spring, and if it be tainted, you will find it by smelling your finger; the flesh of stale pork is sweaty and clammy, that of fresh killed pork, cool and smooth.

Trusler gave advice for carving the roast meat too, and as his book was especially addressed to young people, he gave several pages of advice on how to behave at the dinner table. Methinks we modern folk could learn a little from our ancestors in this regard, so as a refresher I pass on a few tidbits of his advice:

Eat not too fast or too slow.

Spit not on the carpet.

Smell not your meat when eating.

Offer not another your handkerchief.

Not to seem indelicate here, there is a final point of etiquette which I think is very poorly attended to these days, so I am grateful to John T for reminding us:

‘If the necessities of nature oblige you at any time, (particularly at dinner,) to withdraw from the company you are in, endeavour to steal away unperceived, or make some excuse for retiring, that may keep your motives for withdrawing a secret; and on your return, be careful not to announce that return, or suffer any adjusting of your dress, or re-placing of your watch, to say, from whence you came. To act otherwise, is indelicate and rude.

Finally, to avoid a very inelegant temper-tantrum over the lamb instead of pork issue, I give a recipe from the Ladies’ Library manual of 1790, quoted from above:

To roast a Hind-quarter of PIG in Lamb-fashion.

At the time of the year when house-lamb is very dear, take the hind-quarter of a large roasting pig, take off the skin, and roast it, and it will eat like lamb, with mint sauce, or with sallad or Seville orange. Half an hour will roast it.

Have fun.

Tomorrow’s Story …

Cornbread for Hard Times.

A Previous Story for this Day …

“What Does ‘Cooking’ Mean?”

Quotation for the Day …

To do the honours of the table gracefully, is one of the out-lines of a well-bred man; and to carve well, as little as it may seem, is useful to ourselves twice every day, and the doing of which ill is not only troublesome to ourselves, but renders us disagreeable and ridiculous to others. Lord Chesterfield.

The eighteenth century English country parson James Woodforde enjoyed a comfortable living from his curacy in Norfolk. The small holdings attached to his position made his household virtually self-sufficient, and the diary he kept for four decades is rich with detail of village and rural life of the time. He recorded anecdotes about harvesting, pig-rearing, fishing, bread making, preserving, and all manner of other farm and domestic duties. His dinner on this day in 1792 was “boiled Leg of Pork and Peas Pudding, a rost Rabbit and Damson Tarts”, and we can be confident that he knew intimately the source of every ingredient.

What an idyllic life! Producing one’s own natural, organic food in the peace of the countryside, completely in rhythm with the seasons. Fresh, wholesome produce. No added food miles. Simple, healthy, and stress-free.

Unless you are queasy about actually murdering your own sweet, fat little piglet with your own hands of course.

Unless you have no clue as to how to choose a good piece of fresh pork if you are unable to kill your own - thereby risking falling victim to an unscrupulous butcher trying to off-load stock from his unrefrigerated shop.

Unless you are (Heaven forbid!) lacking in that skill essential to well-bred men – skill at carving efficiently and elegantly – thus rendering yourself “disagreeable and ridiculous to others”.

Unless you have a terrible craving for lamb, but it is out of season, and anyway you have to keep eating that damned pig you killed a few days ago, even though you are sick of the sight of pork, because there is a lot left and it won’t keep much longer.

Luckily, there are plenty of eighteenth century manuals to help you, should you decide to take up this idyllic lifestyle.

A book with the instantly reassuring title of The ladies’ library: or, encyclopedia of female knowledge, in every branch of domestic economy ... In which is included a vast fund of miscellaneous information (1790) begins the recipe ‘To Roast a Pig’ with the instruction: ‘Stick your pig just above the breast-bone, running your knife to the heart; when it is dead, put it in cold water for a few minutes, then rub it all over with a little rosin beat exceeding fine and its own blood …’. So now you know how to perform that little duty.

If you are forced to obtain your pork from the market, John Trusler gave plenty of advice in his book The honours of the table, published in 1788.

Pork.

If it be young, in pinching the lean between your fingers, it will break, and if you nip the skin with your nails, it will dent. But if the fat be soft and pulpy like lard, if the lean be tough, and the fat flabby and spungy, and the skin be so hard that you cannot nip it with your nails, you may be sure it is old.

To know fresh-killed pork from such as is not, put your finger under the bone that comes out of the leg or spring, and if it be tainted, you will find it by smelling your finger; the flesh of stale pork is sweaty and clammy, that of fresh killed pork, cool and smooth.

Trusler gave advice for carving the roast meat too, and as his book was especially addressed to young people, he gave several pages of advice on how to behave at the dinner table. Methinks we modern folk could learn a little from our ancestors in this regard, so as a refresher I pass on a few tidbits of his advice:

Eat not too fast or too slow.

Spit not on the carpet.

Smell not your meat when eating.

Offer not another your handkerchief.

Not to seem indelicate here, there is a final point of etiquette which I think is very poorly attended to these days, so I am grateful to John T for reminding us:

‘If the necessities of nature oblige you at any time, (particularly at dinner,) to withdraw from the company you are in, endeavour to steal away unperceived, or make some excuse for retiring, that may keep your motives for withdrawing a secret; and on your return, be careful not to announce that return, or suffer any adjusting of your dress, or re-placing of your watch, to say, from whence you came. To act otherwise, is indelicate and rude.

Finally, to avoid a very inelegant temper-tantrum over the lamb instead of pork issue, I give a recipe from the Ladies’ Library manual of 1790, quoted from above:

To roast a Hind-quarter of PIG in Lamb-fashion.

At the time of the year when house-lamb is very dear, take the hind-quarter of a large roasting pig, take off the skin, and roast it, and it will eat like lamb, with mint sauce, or with sallad or Seville orange. Half an hour will roast it.

Have fun.

Tomorrow’s Story …

Cornbread for Hard Times.

A Previous Story for this Day …

“What Does ‘Cooking’ Mean?”

Quotation for the Day …

To do the honours of the table gracefully, is one of the out-lines of a well-bred man; and to carve well, as little as it may seem, is useful to ourselves twice every day, and the doing of which ill is not only troublesome to ourselves, but renders us disagreeable and ridiculous to others. Lord Chesterfield.

4 comments:

I wonder if my butcher would let me try John Trusler's techniques for testing pork before I buy. Obviously I couldn't try them at the supermarket with the pre-packaged pork - but then I do remember in the supermarket in France all the Camemberts having holes from where customers tested them by poking their fingers in...

Hi Liz, I'm sure that if you keep your fingernails sharp you can stab clear through that plastic wrap on the pork chops!

My uncle kept (and slaughtered) pigs on his farm in Alabama. I've been involved in pig-slaughtering, and it is, indeed, not for the faint of heart. The noise is the worst part in my opinion. On the other hand, it helps if you remember the delicious bacon, ham, sausage, etc. that will result from the necessarily gruesome task. My favorite part of the pig? His tail, of course, roasted over a fire. It was a treat for the kids that we really enjoyed.

Once upon a time, rather recently in terms of all history actually, I was thinking of growing animals on some acreage where we lived. Steer were the norm, but they seemed too big to me. Lambs were an idea, but then I was not truly enchanted by the idea of spending my time wrapping rubber bands around young male lambs in odd places when required. Pigs! It would be pigs. I stood in the hayfield with the farmer down the road and discussed nose-rings and rooting and how to keep them contained well and water supply. It all looked like a great idea (particularly as I know that the pig in literature is a creature very well thought of) till I visited the local slaughter-house where people took their steer and the occasional lamb. They would not do the slaughtering. It was against regulations, somehow, or else it was just not "part of the program". No slaughterhouse in the area would handle pigs, I visited three of them in a fifty-mile radius. One of the owners told me of an old guy that lived "over the hill" (they always live over the hill) that might slaughter pigs if I approached him in the right manner, at the right time of day, with the right magical potion to put in his drink. . .but it was not a very hopeful sort of reference, at all. So no piggery for me.

Adorable things, really, pigs. A shame they taste so good.

I wonder if other parts of the world have this particular challenge in finding someone to do the dirty deed. . .

Post a Comment