Today, January 4th …

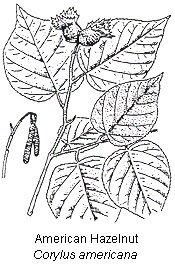

Today, January 4th …For some reason best understood by themselves, mediaeval monks assigned a plant to each day of the year, dedicating it to the Saint of the day. The plant for today, dedicated to St. Titus was the common hazel (Corylus avellana) from which we get the common hazelnut, which is uncommonly good.

As with so many foods from the Plant Kingdom, a true understanding of the hazelnut is as confused by the language as it is revealed by it. The ‘hazelnut’ is also called the cob, cobnut, or filbert and there are both definitive statements or vague insinuations on the part of botanists, horticulturalists and cooks in various geographical locations that one or other provides better eating. Unfortunately there is no consistency in the descriptions and definitions between the various experts in various hazel-growing localities to assist those of us who simply want to ensure that we buy and eat the best variety.

Here are the opinions of two supposed experts of the Victorian era:

From ‘The Market Assistant’ (America, 1867):

Filberts: These nuts are said to be an improved variety of the common hazel-nut, but a great deal larger. The best kind is called the red filbert, known by its crimson skin; another kind, called white filbert, with a yellow white skin; and also another, called the large Spanish filbert. They are found throughout the year; but the new nuts are received only from November to February.

Hazel-nuts, or wild filberts: These are much the shape, form and color of the filbert, but are smaller, thicker shell, and better flavored. They grow on bushes, alongside the borders of the woods and fences, into a cluster of frizzled husks; and when they begin to open, or show the end of the nut, they are fit to eat. They usually appear in August and September.

From Isabella Beeton’s Household Manual (England, 1861):

HAZEL NUT AND FILBERT.--The common Hazel is the wild, and the Filbert the cultivated state of the same tree. The hazel is found wild, not only in forests and hedges, in dingles and ravines, but occurs in extensive tracts in the more northern and mountainous parts of the country. It was formerly one of the most abundant of those trees which are indigenous in this island. It is seldom cultivated as a fruit-tree, though perhaps its nuts are superior in flavour to the others. The Spanish nuts imported are a superior kind, but they are somewhat oily and rather indigestible. Filberts, both the red and the white, and the cob-nut, are supposed to be merely varieties of the common hazel, which have been produced, partly by the superiority of soil and climate, and partly by culture. They were originally brought out of Greece to Italy, whence they have found their way to Holland, and from that country to England. It is supposed that, within a few miles of Maidstone, in Kent, there are more filberts grown than in all England besides; and it is from that place that the London market is supplied. The filbert is longer than the common nut, though of the same thickness, and has a larger kernel. The cob-nut is a still larger variety, and is roundish. Filberts are more esteemed at the dessert than common nuts, and are generally eaten with salt. They are very free from oil, and disagree with few persons.

Whatever they have called them, it seems that humans have been eating hazels for millennia, and cultivating them at least since Classical times, so the relative dearth of recipes for them in historic cookbooks is surprising. John Nott does not use them in ‘The Cooks and Confectioners Dictionary’ (1724), and Isabella Beeton’s only reference is to them is in “a dish of nuts”.

The ever-reliable Cassells’ Dictionary of Cookery (1870’s) comes to the rescue with a single recipe:

Hazel-nut cakes.

Mince two ounces of hazel-nuts and half an ounce of sweet almonds very finely. Add three ounces of pounded and sifted sugar, the white of an egg, beaten to a firm froth, and as much flour as will bind them together. Roll the paste out till it is a quarter of an inch thick, stamp it out in small round cakes, place these on well-buttered tins, and bake in a slow oven.

And from a very elegant era, we have this elegant cake from ‘The Gentle Art of Cookery’ (1920's) by the inimitable Mrs Leyel and Miss Hartley.

Hazel Nut Cake.

A quarter of a pound of finely ground hazel nuts, three and a half ounces of sugar, three eggs, two tablespoonfuls of dry breadcrumbs, and a quarter of a teaspoonful of baking powder.

Beat the yolks of eggs and the sugar for twenty minutes, add the nuts, the breadcrumbs , the baking-powder and the whites of the eggs whipped to a stiff snow.

Fill a buttered cake tin with the mixture and bake for half an hour (or more) in a slow oven.

When cold the cake can be iced over with coffee icing.

Tomorrow’s Story …

The Hired Help.

A Previous Story for this Day …

A Previous Story for this Day …

The iconic Australian cake, the Lamington was the feature of this day's story in 2006.

Quotation for the Day …

New Scientist magazine reported that in the future, cars could be powered by hazelnuts. That's encouraging, considering an eight-ounce jar of hazelnuts costs about nine dollars. Yeah, I've got an idea for a car that runs on bald eagle heads and Faberge eggs. Jimmy Fallon.

Quotation for the Day …

New Scientist magazine reported that in the future, cars could be powered by hazelnuts. That's encouraging, considering an eight-ounce jar of hazelnuts costs about nine dollars. Yeah, I've got an idea for a car that runs on bald eagle heads and Faberge eggs. Jimmy Fallon.

3 comments:

Hi there...I thought the below URL may be of interest to you...I stumbled across it when researching other stuff..

http://www.foodbooks.com/used_cookbooks.htm

Thanks Lee - Thanks for reminding me about this site - I had forgotten it.

Janet

Our family loved the article; would you know more information about how to harvest or eat (ie: must the nuts bee cooked or toasted?).

Post a Comment