Today, November 30th …

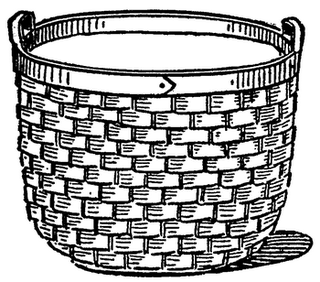

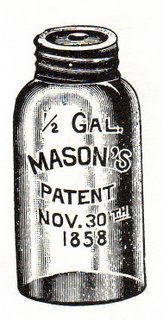

Today, November 30th …If you come across an old jar proudly embossed with the words "Mason's Patent Nov 30th 1858", hope – but don’t assume – that you have found a valuable antique. Although this was indeed the date of issue of a patent to John Landis Mason, jars bearing the date were produced by the millions until the 1920’s. The sort of success that every inventor dreams of, Yes?

The application for U.S Patent number 22,186 said:

"Be it known that I, John L. Mason, of the city, county, and State of New York, have invented new and useful Improvements in the Necks of Bottles, Jars, & especially such as are intended to be air and water tight, such as are used for sweetmeats, & of which the following is a specification….”

The system of excluding air to aid preservation had been learned over many centuries of trial and error (and no doubt many cases of serious food poisoning), and even at the time of John Mason’s patent there was no scientific understanding of the process - this came a few years later with Pasteur’s “germ theory”.

John Mason’s innovation consisted of a shouldered glass jar with a threaded edge and a corresponding threaded metal lid, which was indeed a new and useful improvement over the existing methods of sealing with a layer of fat, or “bladder”, or linen, or cork, or wax, or a combination of these with or without string or wire ties. Over the next few decades the basic Mason jar design features were tweaked with glass or lined metal lids and rubber gaskets such as are familiar today. The new jars were responsible for the huge boom in home preserving which lasted well into the twentieth century when domestic freezers became common.

In spite of its eventual huge impact, the patent expired before John Mason was commercially successful, and he apparently died a pauper, his only legacy being the association of his name with the generic product. What happened to John Mason was what we now call “generic trademarking”, that is, the association of The Product with The Brand, and something a good trademark lawyer (if there were such people then?) could have helped him avoid. He is in good company historically. The same thing happened to with zippers, brassieres, aspirin, cellophane, thermos flasks and a host of other eminently copiable ideas.

There are some cooks with pure and nostalgic hearts who still preserve surplus produce the old way, and in their honour I provide several nineteenth century recipes which are eminently suitable for processing in jars. The recipes chosen are for green tomatoes, for no better reason than that they are seriously under-used here in Australia.

Mixed Pickles.

One peck of green tomatoes, half a peck of onions, one pint grated horseradish, half a pound white mustard seed, half a pound of unground pepper, one ounce each of cinnamon, cloves and turmeric, and two or three heads of cauliflower; tie the pepper, cinnamon and cloves in a thin muslin bag, place all the ingredients in a granite ware kettle, cover with vinegar and boil until tender. Can put while hot in glass fruit jars. [U.S Newspaper recipe 1879]

Green Tomato Sauce.

Two gallons green tomatoes sliced without peeling, twelve large onions also sliced, two quarts best cider vinegar, one quart brown sugar, two tablespoonfuls ground black pepper, one tablespoonful allspice, one tablespoonful cloves, both ground. Mix all together and stew until tender, stirring often to prevent scorching. Put up in small jars for convenient use. A nice sauce for all kinds of fish and meat. [U.S Newspaper recipe, 1882]

Green Tomato Preserves.

Take seven pounds of nice, even-sized, small, green tomatoes, six pounds of sugar, three lemons, five cents’ worth of cloves and cinnamon mixed (use only half of this) and one-half ounce of whole ginger. Pierce each tomato with a fork, heat all together slowly and boil until the tomatoes look clear. Don’t use the seeds of the lemons. Take out the tomatoes with a perforated skimmer and lay on large platter and then fill in glass jars. Boil the syrup until very thick,pour over the tomatoes hot, and seal. This tastes like fig preserves. ["Aunt Babette's" Cook Book: Foreign and domestic receipts for the household…” c1889]

Tomorrow’s Story …

Diplomatic Drinks and Dessert.

A Previous Story for this Day …

"Sending home the Bacon" was the story for this day in 2005.

Quotation for the Day …

Alexandra often said that if her mother were cast upon a desert island, she would thank God for her deliverance, make a garden, and find something to preserve. Preserving was almost a mania with Mrs. Bergson. Stout as she was, she roamed the scrubby banks of Norway Creek looking for fox grapes and goose plums, like a wild creature in search of prey. She made a yellow jam of the insipid ground cherries that grew on the prairie, flavoring it with lemon peel; and she made a sticky dark conserve of garden tomatoes. She had experimented even with the rank buffalo-pea, and she could not see a fine bronze cluster of them without shaking her head and murmuring, "What a pity!" When there was nothing to preserve, she began to pickle. Willa Cather, 'O Pioneers!'.