Today The Old Foodie is one year old. Her body is considerably older, and the blog is slightly younger, but these events will be celebrated in their own time.

To celebrate The Old Foodie birthday, and to thank you for your enthusiasm and kind comments, The Old Foodie is going to give a prize for the first correct answer drawn out of her biggest mixing bowl, to a ten-question quiz.

The Prize:

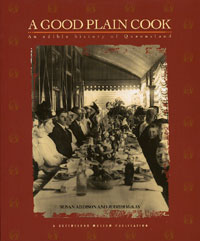

The Prize:The prize is a copy of “A Good Plain Cook: An edible history of Queensland” by Susan Addison and Judith McKay, and published by the Queensland Museum. If you have ever wondered how to roast bandicoot or wallaby, or use dry coffee as a preservative, or make Poor Man’s Goose, then this is the book for you. If not, it also has recipes for Anzac biscuits, Miss Schauer’s Cup Cake, and pikelets and such like, which are sure to please. The book is delightfully illustrated with photographs, advertisements and images from by-gone days.

The Conditions: [Note: changed deadline]

In order not to penalise those of you around the globe who will be sleeping soundly at that time, it will not be “first correct answer wins”, it will be “first correct answer drawn out of my largest mixing bowl wins”. I will give until "the end of the weekend" - which I have designated as Monday 6th November 5 pm Australian Eastern Standard time (2 am in New York and 7 am in London).

I will print off all correct answers and will pick a suitably qualified person to draw out a winner.

Please respond by email to THE OLD FOODIE, or post your answers in the comments to this post.

The winner will be announced on Monday morning, Australian Eastern Standard Time.

The Questions:

1. When is “Split-Stomach Day”?

2. What is the principal ingredient of “black butter”, as enjoyed by Jane Austen?

3. The first cookbook to give instructions for the now traditional wedding cake’s almond icing plus white icing, was …… ?

4. What year was “Vegemite” launched?

5. When is Woodruff Wine traditionally drunk?

6. What did Edmund Hilary and Tensing Norgay eat at the summit of Everest in 1953?

7. Whose coronation is associated with the dish “Coronation Chicken”?

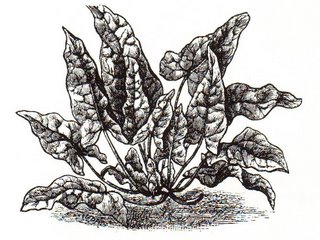

8. What is the “Scarcity Root”?

9. Who is “Chicken Tetrazzini” named for?

10. What is “Sack” better known as today?

There, that wasn’t too hard, was it? If you’ve been paying attention, all the answers are in an Old Foodie story on this blog.

P.S. There is a also real food story for this day, with a recipe of course – you will find it by scrolling down a little further ….