Today, July 14th …

Today, July 14th …Today is the anniversary of the day in 1789 that the oppressed peasants rose up and stormed the terrible prison in Paris called the Bastille, liberating its political prisoners and turning the tide of history inevitably towards the founding of the Republic. No - actually, it was the day that a rioting mob, seeking the weapons stored there, managed to overcome about 112 guards (80 of whom were

invalides) and in the process managed to liberate the seven remaining prisoners – four forgers, two madmen, and one dissolute young aristocrat placed there by his family. The real story notwithstanding, the events became symbolic of the founding of the Republic, and it is the National Day of France.

Naturally then, it is a day for French food, for as Jean Anouilh said “

Everything ends this way in France – everything. Weddings, christenings, duels, funerals, swindlings, diplomatic affairs – everything is a pretext for a good dinner”. We have the pretext, but what shall we chose from the classic French repertoire for our dish of the day?

The French gourmet Grimod de la Rèyniere who lived through it all supposedly said, with reference to the French Revolution, and with great relief, something along the lines of: “

If it had lasted any longer, we might have lost the recipe for fricassée of chicken” It seems apt to choose this dish then, and to make it even more appropriate, the good Baron Brisse (1868) gives us a version named for one of the mistresses of Louis XV:

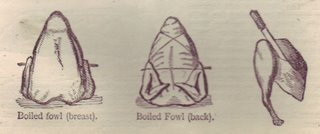

Fricassée of fowls à la Du Barry.

Cut up your fowls into joints, and soak for an hour in cold water, which change two or three times; drain, and dry them carefully in a cloth, and cook in water; as soon as it begins to boil, remove the pieces of fowl, and pass the liquor through a tammy. Warm a lump of butter, some scraped bacon, and a slice of Bayonne ham over a slow fire; when quite hot, add the pieces of fowl, and as soon as they begin to stiffen, stir in a tablespoonful of flour; take the saucepan off the fire, moistent the fricassée with equal quantities of stock, and the liquor in which the fowls were boiled; season with a bouquet of mixed herbs, an onion stuck with cloves, and boil for three quarters of an hour, remove the onion and herbs, and if the sauce is not sufficiently reduced stir in some yolks of eggs, and serve.

Tomorrow: Walthamstow Wine.

An extra treat for Bastille Day ...A special day sometimes justifies a special treat, so I give you a number of quotations today, each one giving a different perspective on the French and their food. Please comment, if you feel so inclined, on the one you feel most closely matches your own feelings, and of course, please submit any others you may know.

“Food: Part of the spiritual expression of the French, and I do not believe that they have ever heard of calories.”

Sir Beverley Baxter.

Thanksgiving is America's national chow-down feast, the one occasion each year when gluttony becomes a patriotic duty. In France, by contrast, there are three such days: Hier, Aujourd'hui and Demain."

Michael Dresser.“The French are not rude. They just happen to hate you. But that is no reason to bypass this beautiful country, whose master chefs have a well-deserved worldwide reputation for trying to trick people into eating snails. Nobody is sure how this got started. Probably a couple of French master chefs were standing around one day, and they found a snail, and one of them said: "I bet that if we called this something like `escargot,' tourists would eat it." Then they had hearty laugh, because "escargot" is the French word for "fat crawling bag of phlegm." ”

Dave Barry.“Bouillabaise is only good because cooked by the French, who, if they cared to try, could prepare an excellent and nutritious substitute out of cigar stumps and empty matchboxes.”

Norman Douglas.

“Mayonnaise: One of the sauces which serve the French in place of a state religion.”

Ambrose Bierce.

“We heard one evening, under the eye of the imperturbable Paul, a foreign lady ask for a milk chocolate drink to accompany a fillet of sole Cubat, the chefs specialty. Sacrilege! Just as well that Marcel Proust and Boni de Castellane were not here to see that.”

Simon Arbellot.

"If any one element of French cooking can be called important, basic and essential, that element is soup."

Louis Diat.

"Never forget that the pheasant must be awaited like the pension of a man of letters who has never indulged in epistles to the ministers nor written madrigals for their mistresses."

Francois des Essarts

“A man should not so much respect what he eats, as with whom he eats.”

Michel Eyquem de Montaigne.

"The only cooks in the civilized world are French cooks. … Other nations understand food in general; the French alone understand cooking, because all their qualities - promptitude, decision, tact - are employed in the art. No foreigner can make a good white sauce."

Louis Victor Nestor Rocoplan.

“To be a gourmet you must start early, as you must begin riding early to be a good horseman. You must live in France, your father must have been a gourmet. Nothing in life must interest you but your stomach.”

Ludwig Bemelmans.

“Without butter, without eggs, there is no reason to come to France”.

Paul Bocuse.

“In France, cooking is a serious art form and a national sport”.

New York Times journalist, 1986.

“Truffles are a luxury, and the first requirement of a luxury is that you should not have to economize."

James de Coquet.

"Light, refined, learned and noble, harmonious and orderly, clear and logical, the cooking of France is, in some strange manner, intimately linked to the genius of her greatest men."

Marcel Rouff.

Today, July 31st …

Today, July 31st …