Today, April 28th …

Today, April 28th …On April 28th 1873 the Imperial Hotel in Vienna was officially inaugurated, which means that today is the birthday of the Imperial Torte, one of the most famous cakes in a city of famous cakes. It is a pleasant little story.

Emperor Franz Joseph I was to officially open the hotel, and knowing his love of sweet things, the pastrycooks of the city had spent the preceding day competing to produce the masterpiece that would catch his eye. One young apprentice also wanted to make something for his beloved Emperor, and sneaked down to the kitchen during the night. All of the usual round baking pans had been used, so he came up with the first square chocolate cake in Vienna: a multi-layered torte with five thin layers of almond paste, a “slight hint” of cocoa crème, and a milk-chocolate glaze. Naturally it was the one that the Emperor chose, and the rest, as they say, is culinary myth-tory.

Sadly, the recipe is a closely guarded secret, so you will have to go to Vienna to taste the real thing, but do not despair – there is an alternative cake with an alternative story.

Franz Joseph also loved the ladies, and like many royal males in history, had an actress for a mistress. Katharina Schratt had a villa close to his summer residence – rumour had it that they were connected by a secret passage – and she always made sure she had a special Gugelhopf made for him. Hence, the local euphemism for the Emperor’s visits to her became “he has just ravished another Steinkogler Gugelhupf!”.

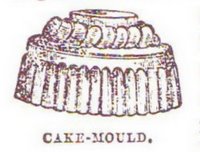

Steinkogler Gugelhupf

150gm butter, 100 gm sugar, 6 egg yolks, 350gm flour, approx 250 ml milk, 30 gm yeast, 2 egg whites, pinch of salt, almond slivers

sugar to serve

Combine yeast, a small amount of warm milk, a pinch of sugar, and 1 tabs flour in a mixing bowl and keep warm. Then melt butter in a pan, and stir until foamy. Now mix in the sugar, egg yolks, flour, milk, pinch of salt, and the yeast mixture. Stir vigorously until the batter forms bubbles and no longer adheres to the sides. Beat the eggwhites until stiff and fold in. Grease a Gugelhupf mold with butter, dust with flour and sprinkle in the almond slivers. Put in the batter, cover and let rest in a warm location. Bake 1 hour at 170-180oC, sprinkle with sugar and serve.

From ‘Imperial Austrian Cuisine”; Renate Wagner-Witttula.

On Monday: Spring rites and Workers rights.

Above and Beyond ...

For an 1870's recipe for "Kouglauffe" from an English cookbook, go to the Companion to the Old Foodie.

Quotation for the Day …

There is no sincerer love than the love of food. George Bernard Shaw.